Delays to patient care can be damaging in more ways than one. While clinical outcomes may worsen over time, longer waits for diagnosis and treatment of cancer can also have both physical and emotional impacts on patients.

The impact of Covid-19

The pandemic has affected many areas of people’s lives, including their access to and use of health services such as cancer screening and routine medical appointments.

Australia’s three national cancer screening programs were disrupted initially, but have since caught up in terms of the number of people screened. While BreastScreen services were initially suspended from late March to late April/early May 2020, screening continued during Victoria’s second wave, and the number of screening mammograms performed was significantly increased during the second half of 2020 to make up for the shortfall.

There was no suspension of the National Cervical Screening Program or the National Bowel Screening Program. The National Bowel Cancer Screening Program has broadened its target age groups in recent years, which has led to home-based testing kits being sent to more people, and data from the AIHW shows that the number of test kits returned in 2020 was similar to the number in 2019. So the impact on screening over time appears to be relatively low.

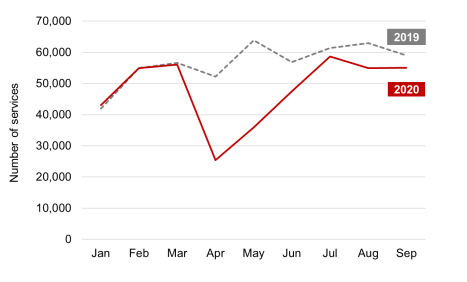

However, when it comes to diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, data from Cancer Australia show a reduction in procedures relating to skin, breast and colorectal cancers between March and May 2020 compared to the same months in 2019. Although services are approaching 2019 levels, a backlog remains from the initial suspension period in March-May last year.

Colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy cancer investigation procedures in 2019 and 2020. Source: Data from Cancer Australia

The number of colorectal investigations performed in April was around half of those undertaken in March, with colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies decreasing by 55%. Looking at the period January to September 2020, compared with the same period in 2019, there were 15% fewer colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies, which equates to 78,048 fewer procedures.

There were three main factors causing the reduced number of diagnostics and tests; patients being cautious, a general disruption to services or enforced restrictions, and reduced system capacity due to social distancing and longer turnaround times to allow for stricter infection control procedures.

Delays in the cancer diagnosis and treatment journey are likely to have consequences for many months to come. While the pandemic has certainly caused disruption, it is not the only reason backlogs have formed.

The only constant is change

Aside from Covid-19 and other disruptive events, a key reason patients experience delays to procedures or uncertainty around waiting times is politics. Changes to both local and national governments inevitably lead to changes to policies and priorities, often affecting waiting times for diagnostic procedures and elective surgery, since healthcare delivery plans rely on annual or one-off funding programmes.

This particularly applies to procedures alleviating long-term conditions, such as hip- and knee replacements or cataracts, but not exclusively; changing priorities and budgets also impacts on diagnostic activity such as endoscopies and scans.

For example, there has been four restructures of the health service in Tasmania in the past decade, and more than 10 reports have been issued in that time with recommendations for how the state’s health system should be run.

Uncertainty caused by changes in policy affects not only patients but also healthcare staff. In a recent ABC News article, Tim Jacobson, state secretary of the Health and Community Services Union describes how staff are suffering ‘reform fatigue’ and frustration at the apparent lack of a clear implementable long-term plan.

Funding should be guaranteed so that long-term plans can be implemented. A clear strategy for health needs to be a priority at all times, and not just on the agenda at election time.

The wait is unknown

Perhaps the issue causing the most distress for patients is that the wait they are facing is often unknown. Already before the pandemic, some people had waited a long time for a procedure, but during the pandemic the speed at which lists can be worked through has become even more unpredictable.

Uncertainty can have adverse impacts on mental health for both patients and carers, in particular those with high levels of anxiety. There are calls to increase the transparency within health services and inform patients about the clinical prioritisation methodologies used, as well as keeping patients up to date with estimates of when their procedure might go ahead.

A recent paper written by Policy Exchange in the UK highlights the issue of patients being ‘left in the dark’ and concludes that swifter diagnosis is needed. Giving patients the information and ability to manage as much of their own patient journey as possible may include allowing patients to make their own appointments online without needing to call the hospital, which reduces the administrative burden on staff while boosting patient choice and sense of control.

As well as increasing transparency and improving communication, patients may also need to be supported while they wait.

Poorer clinical outcomes

Cancer can take a long time to develop, and finding it at an early stage means a better chance that treatment will be effective and that the patient will survive.

The impact of late diagnosis on the treatment and prognosis for some cancer patients is significant. A study published in the Lancet in August 2020 found that for some cancers, including those of the colorectum, oesophagus, lung, liver, bladder, pancreas, stomach, larynx, and oropharynx, a three-month delay to diagnosis is predicted to result in a reduction in long-term (10-year) survival of more than 10%, in most age groups.

There is increasing concern about the longer term effects of the pandemic, with patients presenting later with symptoms, treatment being delayed and requiring more intensive management, and outcomes being severely affected. Risks to patients increase and survival rates may be affected.

The pandemic risks reversing the current positive trend in survival rates. The 5-year relative survival rate for bowel cancer has increased from 52.3% to 70.3% between 1987-1991 and 2013-2017, a development which can partly be attributed to higher rates of screening, meaning more cases are detected early.

It is clear that cancer screening programs reduce mortality. Data from AIHW showed that people diagnosed through the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program had a 59% lower risk of dying from bowel cancer than people who had never been invited to screen. Prior to the pandemic, women diagnosed with breast cancers through BreastScreen Australia also had a 69% lower risk of dying than those who had never screened. Cervical cancers detected through cervical screening had an 87% lower risk of dying than women who had never had a pap test.

The mental health burden

Regardless of clinical risk to patients, uncertainty and delayed diagnosis can have other negative impacts on patients. A recent global scoping review looked at the mental health impact of waiting for key procedures and the effect of various coping strategies.

The review included 51 studies covering organ transplants, surgery and cancer management, and found that both patients and caregivers experienced anxiety, depression and poor quality of life, and that these deteriorated with increasing wait time. The impact of waiting on mental health was greater among women and new immigrants, and those of younger age, lower socio‐economic status, or with less‐positive coping ability.

In addition, participants of qualitative studies specifically mentioned uncertainty around the length of the wait as a key concern. They also had concerns about whether their health was deteriorating to such an extent that it might affect their eligibility for the procedure or even clinical outcomes.

Patients spoke of restrictions to their ability to perform physical functions due to being less mobile or pain, and being unable to work or take part in social activities. Many also felt their life was put on hold as they were constantly on alert for a phone call, and unable to make future plans due to uncertainty about timing of the procedure.

Study participants referred to waiting as a ‘daily emotional roller‐coaster’ and an ‘immense struggle’. Exhaustion increased over time, reducing motivation to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and turning hope into despair. This could actually increase the pressure on the health system as a whole.

Strategies to support patients

As well as an adverse effect on quality of life, patients and caregivers also felt their trust in the health system had been eroded. There is a clear need to implement strategies that support the mental health of wait‐listed patients and caregivers, both now and in the future.

The aforementioned study looked at the effectiveness of various patient‐centred mitigation strategies that could be applied in the context of Covid-19. It found that therapy and coping skills training in the form of regular multiple in‐person or online classes over many months did not consistently reduce anxiety or depression, or improve quality of life. Instead, patients said that even if waiting times could not be reduced, simply acknowledging the burden of waiting, receiving peer support and periodic communication to update wait‐list status could alleviate the mental health impact of waiting and assure them they had not ‘fallen through the cracks’. Participants wanted periodic updates from health professionals that included the reason for delay, their position on the waiting list, prioritisation criteria and estimated procedure date.

Online patient portals can be used to improve patient experiences, behaviour and clinical outcomes as it allows patients to be involved in their own care and promotes continuity of care. Automating wait‐list communication around delays to affected patients could reduce uncertainty for patients, while at the same time alleviating strain on clinicians and their staff who are unable to predict when procedures will be scheduled but are still required to respond to phone calls from anxious patients or caregivers.

Cancer won’t wait

The ongoing impact of Covid-19 and the resulting delays in diagnosis are likely to impact on cancer treatment and survival for many years to come. The long-term effects will not be known for some time, especially as the country remains vulnerable to further outbreaks, and capacity to undertake procedures remains limited.

Building lasting resilience into healthcare systems and preparing for post-pandemic recovery is key. According to a recent report entitled ‘Cancer Won’t Wait’ by IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science a resilient healthcare system is one that can build and maintain a high level of health capacity in times of shock through focusing on key areas: flexibility in capacity in hospitals, orientation to improve patients’ outcomes, mobilisation of resources such as testing, disease prevention, availability of therapeutic options, and adoption of technology.

Aside from the human cost, there is a cost to the healthcare system in terms of an added burden on staff and capacity required in cases where the waiting list is allowed to grow. Already strained health systems may face added future pressure to manage other mental health needs emerging from the pandemic. The uncertainty around waits also represents an unknown clinical risk to the health service, and a risk that cancers diagnosed at a later stage will need more complex treatment.

Part of the cost to the healthcare system is that patient trust is being eroded. The study reported that participants felt angry that they were not considered a priority and frustrated with the lack of information, and ambiguity and perceived inequity in prioritisation. Clearly, reassurance and effective communication goes a long way. But to markedly improve patients’ experiences over time, further capacity to undertake more procedures – and greater flexibility – will need to be added.