Although it is more than ten years until Brisbane will host the 2032 Summer Olympics, planning is already underway. The Olympic and Paralympic Games present an enormous logistical challenge for the host city, and evidence from previous Olympics show that building redundancy, resilience and flexibility into capacity plans is essential.

Brisbane 2032 will be the third Summer Games held in Australia, following the games in Melbourne in 1956 and in Sydney more recently in 2000. The Brisbane bid featured a strong focus on sustainability, with organisers stating that over 80% of the infrastructure needed to host the games already exist or are in the process of being extended or upgraded.

Some new construction will take place; the main Olympic Stadium, the Brisbane Cricket Ground, will be expanded from a capacity of 42,000 seats to 50,000, and temporary venues will be constructed around the city. A ‘Brisbane Live’ precinct will house a new arena, which will be used for events such as aquatics, and investment in transport projects include a new railway station.

Venues will be located in three zones: Brisbane, Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast. Although most of the new venues being created will be situated in the Brisbane Zone, event venues will be spread out across the region, including in the cities of Cairns, Toowoomba, Townsville, Sydney and Melbourne. This wide geographical spread could create particular challenges for the organisers when it comes to access to medical facilities and healthcare planning.

Healthcare during Olympic Games

Health service planning for such an extraordinary event has to begin many years before the opening ceremony. As well as preparing for any potential injury or illness that an athlete may suffer, organisers also need to plan for illnesses and injuries among spectators, and facilities also need to cater for coaches, officials, national delegates, support teams, the media, workers and volunteers.

The host country is normally responsible for providing services to all residents of the Athletes’ Village, usually through establishment of a ‘polyclinic’, but it is up to each national organisation to decide whether they will provide their own medical care to their athletes and to what extent they will rely on the host country’s services.

It is usually in the host’s interest to provide extensive facilities for athletes on site to ensure ‘business as usual’ for local residents that need to use existing health facilities. Therefore, the medical needs of athletes are mostly dealt with in the facilities on site and rarely result in transfer to outside hospitals, although there are occasions where a team’s medical provision is not sufficient and patients need to be transferred to a local hospital.

The creation of polyclinics are just one aspect of the health service challenge. Appropriate medical care – at the very least first aid – must be provided at the various Olympic venues, including at training facilities and any affiliated hotels. The capacity of existing health facilities in the vicinity of venues may need to be upscaled or the scope widened to cater for the visitor population.

The importance of early planning and effective communication between stakeholders, in particular local health service organisations and event organisers, is well documented. Event organisers will need to coordinate with local hospitals, clinics and ambulance and emergency responders to facilitate transfers, referrals or other necessary services.

Plans for a major emergency or a mass casualty incident are also needed. With so many people descending on a concentrated area at the same time, modelling for peak usage of any medical facility in the area, including the polyclinic, is necessary to ensure existing facilities can cope with the potential increase in attendance in the case of a major outbreak.

The size of the healthcare effort

A lot can be learned from previous Olympic events – and the organisers of Brisbane 2032 are fortunate to be able to learn from a relatively recent games in Sydney – but each Olympics is a unique event with its own particular set of challenges and possibilities. Olympic Games are also different to other types of mass gatherings is limited; they take place over a long time period (unlike concerts and other sporting events), they involve mainly young and healthy spectators and tend to be located over a number of often highly dispersed sites.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Health Protection Agency (HPA), a key aspect of planning is to focus on enhancing and improving existing systems to ensure they can be upscaled to cope with the extra demand, rather than treating the Games as a separate event. To do this effectively, establishing and communicating on the baseline for certain incidents, e.g. average number of cases for that time of year, is vitally important.

Looking at previous Olympic Games can help with an understanding of scale. The London 2012 Olympics had over 10,000 competing athletes from 204 separate nations, along with an estimated 20,000 accredited media members and a workforce of about 200,000 people, including paid workers, volunteers and contractors. As for spectators, around 8 million tickets went on sale. The polyclinic in its Athlete’s village recorded just over 3,200 encounters, including medical consultations, radiology/pathology investigations and prescriptions dispensed.

The Rio 2016 Organising Committee sold 6.2 million tickets and a total of 1.17 million tourists visited Rio de Janeiro during the Games. Its central polyclinic recorded around 7,000 patient encounters during the period, and more than 1,500 diagnostic procedures such as MRI scans, Ultrasounds and X-Rays, were performed. The evaluation of the recent Tokyo games is not published yet.

Brisbane may not normally receive as many visitors as London or Tokyo. The Games in PyeongChang, Korea and Vancouver in Canada were spread out over a number of locations, and in both cases, two polyclinics were established in key locations, rather than one. Flexible infrastructure was also used – the Vancouver Games used two 54-foot trailers that contained operating rooms, trauma beds and blood supplies.

The key challenges

There is a need to simultaneously deliver ‘business as usual’ for local populations, enhanced capacity for visitors and official healthcare pathways for athletes and their support teams. At the same time, mass gatherings have the potential to bring both health and security risk.

Given the numbers of people crowding into a city or a region during the Olympics, it is inevitable that a variety of infectious diseases are of concern to organisers and medical teams. People from areas with high incidence rates of some transmissible diseases might also mingle with people from nations where those diseases are less common, introducing further health risks.

Given the numbers of people crowding into a city or a region during the Olympics, it is inevitable that a variety of infectious diseases are of concern to organisers and medical teams. People from areas with high incidence rates of some transmissible diseases might also mingle with people from nations where those diseases are less common, introducing further health risks.

On the other hand, major incidents at previous Games have been rare, and illness and injury rates have been relatively low, although peak usage rates can be high during certain competitions, both for athletes and spectators. As a result, it is difficult to achieve the optimal capacity level, and it is easy to end up with a huge amount of unused capacity – or worse, not enough.

Communication between event organisers and local healthcare organisations have presented a challenge at previous Olympics – notwithstanding any language barriers. Collaborating and involving local healthcare organisations in the planning and testing of scenarios is necessary to avoid duplication of efforts and potential issues falling through the gap.

An important aspect for host cities of recent and future Olympic Games is to avoid wasting resources and achieve value for money – as well as lasting benefit for the host country in the longer term. The aim is to avoid spending large amounts of money on infrastructure or buildings that will be discarded or remain unused once the event is over.

Additional challenges include ensuring there are effective systems for creating and sharing medical records, referrals, prescriptions and payment for medical services. All national team medical service providers are subject to the rules and licensure regulation of the host country and temporary licensing is usually restricted to the care of the team’s own athletes and entourage.

The polyclinic

It has become standard practice to establish one or more polyclinics for athletes and their support teams. Polyclinics offer primary care and a range of services including sports medicine, physiotherapy, optometry, ophthalmology, dental care, medical imaging and podiatry. Additional specialist expertise available on call can include orthopaedics, cardiology, obstetrics and gynaecology, dermatology, surgery, neurology and gastroenterology.

Often, there is also a pharmacy, laboratory, and a radiology suite with X-ray, ultrasound, MRI – and sometimes CT – scanners. The polyclinics are aimed at making an accurate diagnosis quickly to allow for competent treatment of the athletes so that they may return to their competition as soon and as safely as possible.

Since services at the polyclinic are provided free of charge to national delegations, and this provides a chance for those with poorer health systems to get access to dental care, ophthalmic services and scans, in particular. Polyclinics are also used for preventative measures such as sport massages.

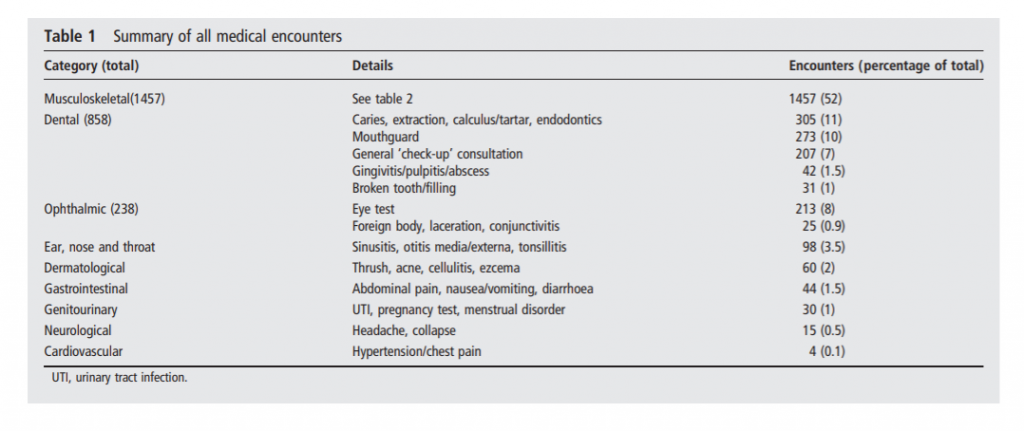

Summary of all medical encounters – London 2012 Olympics polyclinic. Source: An analysis of usage of the Olympic Village Polyclinic by competing athletes.

Data collected by the IOC Injury and Illness Surveillance System shows that the incidence of illness among athletes during the Rio Games was 5% – the lowest rate since reporting started in 2010. At London 2012 the illness rate was 7% among athletes, while Sochi 2014 reported an 8% illness rate. Respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases account for a majority of the reported illnesses, but in terms of overall attendances, the majority are musculoskeletal. At London 2012, these accounted for 52% of polyclinic encounters (it should be noted that the category included sports massage), followed by dental procedures accounting for around 30% (but included mouthguard fitting) and ophthalmic services with 8%.

Doping unfortunately affects every Olympic Games, and regular testing of athletes and analysis must be undertaken. All national sports organisations must adhere to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)’s code when competing in sanctioned sporting events.

For scale, the Rio 2016 Polyclinic was staffed by 180 medical professionals who covered 3,500 square meters and 160 rooms. The previous record of 650 patient consultations in one day during the London 2012 Olympic Games was surpassed by the Rio 2016 Polyclinic, which treated 900 patients in one day.

Services can vary – for example, Tokyo’s polyclinic did not offer CT scanning at the polyclinic but opted to transfer patients to the dedicated Olympic hospital. At the Vancouver 2010 Games, two major clinics were established, one in Vancouver and the other in Whistler, each measuring 10 000 square feet, covering an estimated 9,000 encounters.

When venues are more dispersed, Olympic organisers rely on local healthcare infrastructure to a greater extent, but in return, the additional burden in each location is reduced, lowering the risk of local services being overrun. Temporary healthcare facilities, such as modular clinics or mobile operating rooms, are also particularly useful where venues are spread out over a wider area. In addition, some sporting events carry higher risk of injury than others, and by using mobile or modular clinics in key locations, medical care can be provided wherever it is needed the most on any given day.

Visitors’ healthcare

Although ticketed spectators are a part of the Games, the expectation is that they will be treated within the usual healthcare system. Medical stations open to spectators generally offer first aid only; any illness or injury that needs treatment will be taken care locally at a health centre or public hospital.

In terms of capacity planning, it is all about the expected peak in attendances. With some sports carrying a higher risk of injury, and the heightened potential for infectious diseases to spread, the estimated peak can sometimes be very high. Data from previous Winter Games has shown that daily encounters at the polyclinic can be managed by not scheduling several high-risk events on the same day. The same goes for spectators – some competitions accommodate larger crowds than others.

At London 2012, health service planning was based on the assumptions that demand would be similar to a mild Winter (traditionally a time of high pressure) and an expected increase in alcohol or substance misuse related attendances at emergency departments. However, evidence from previous Games shows that alcohol and drug related attendances are lower than for other events of a similar size.

Olympic Games inevitably lead to a large increase in visitors to a concentrated area, putting pressure on existing healthcare infrastructure. Flexible solutions such as mobile or modular minor injuries units or clinics can help keep much of the pressure off local facilities, in particular in rural areas where existing facilities are not dimensioned for the influx of visitors to the area.

Impact on local healthcare infrastructure

With the need for local health services to meet the potentially raised demand for healthcare, how will primary care facilities and hospitals in the local area be impacted? It is a good question. Modelling and evaluation exercises from different Olympic Games are of limited use as there are many variables, and different locations have different levels of pre-existing surge capacity.

A major city may have a large amount of capacity to accommodate visitors all year round, while other destinations make additional capacity available on a seasonal basis – but some event locations may not be able to access this. In a city like London, visitors to the Olympic Games can replace other visitors; those not willing or able to attend the Olympics may avoid visiting during that period due to inflated costs and limited availability of travel and accommodation, and longer queues for attractions.

Evidence from the 2012 London Olympics suggests that hospitals in North East London saw a 5.2% decrease in the mean daily number of emergency department presentations during the Games, while emergency departments near Olympic venues outside of London saw a 4.8% decrease. Walk‐in centre attendance in North East London also decreased in July 2012 compared to the same month in both 2010 and 2011.

That is not to say there was no impact on local healthcare. The need to prepare for every eventuality led to a tendency to over-estimate demand – particularly for emergency care – and this need for preparedness meant capacity, in terms of both staff and facilities, had to be on stand-by and may be needed at very short notice.

An independent review of the healthcare effort at London 2012 found that, while NHS London tried to promote proportionality around the scale of routine services required, trusts tended to make their own calculations or to use the upper boundaries of the NHS’s predictions as a starting point, and over-preparing. But while no major incidents were encountered during the Games, it is understandable that concerns about potential disaster overrode evidence-based models on likely levels of demand.

A need for flexibility was also identified; the organisers needed to be able to deal with unforeseen changes, especially given the long planning timescale. Greater use of flexible healthcare infrastructure would have meant enough surge capacity was available in the event it was needed, in the location it was needed, without impacting on local clinics and hospitals.

What health infrastructure will be needed?

Alongside additional medical staff and volunteers, there will be a need to upscale physical capacity to ensure both athletes and visitors are adequately covered. Flexible healthcare solutions are ideal for large scale events; with venues spread out over different areas, health service provision can be focused on where it is needed the most. Mobile facilities can be moved between areas or be placed in strategic positions in between key event locations.

Lab capacity will also need to be upscaled. During the Games, labs need to deliver both ‘business as usual’ and frontline public health diagnostics, as well as rapid testing and reporting to identify potential outbreaks of infectious diseases and routine testing.

Modular semi-permanent healthcare buildings can be used to create a polyclinic or other larger healthcare facility – and not just as a temporary solution. The lifespan of appropriately maintained modular buildings can be 60+ years, so they can help create a legacy that can be used by the local population after the Olympics. The facility along with the equipment inside it could be repurposed and relocated to fit the needs of the local health service once the Games are over.

The starting point for plans to deliver routine and emergency services for both the local and visiting population must be baseline capacity. Extending and enhancing existing systems and practices will be more sustainable than building everything from scratch, and will benefit the local population.

Early planning is also essential, along with the need to build in redundancy, resilience and flexibility into capacity planning and to prepare for the unexpected. Flexible healthcare infrastructure can provide that extra flexibility and resilience and when no longer needed, a mobile or modular facility can be used to improve health service delivery for the local population – or be moved to another location to provide extra capacity for the next event.

Estimating healthcare demand may be one of the biggest challenges of hosting the Olympics. Balancing the potential risk of an outbreak or emergency with evidence-based modelling is key to ensuring there will not be an unacceptable cost to people’s health; regardless of whether they are competing, visiting or just happen to live locally.

—

Sources:

PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games and athletes’ usage of ‘polyclinic’ medical services https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6733333/

2014: IOC Injury & Illness Surveillance Study: protecting the athletes’ health https://olympics.com/ioc/news/ioc-injury-illness-surveillance-study-protecting-the-athletes-health/

2019: Olympic Games: Special Considerations—Medical Care for Olympians https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332390876_Olympic_Games_Special_Considerations-Medical_Care_for_Olympians

Wikipedia: 2032 Summer Olympics https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2032_Summer_Olympics

Brisbane’s 2032 ‘climate-positive’ Olympics commitment sets high bar on delivering sustainable legacy https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-11-08/qld-olympic-climate-positive-brisbane-2032-games-commitment/100598202

2013: Healthcare challenges at an Olympic Games https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/47/7/401

2013: The London 2012 Summer Olympic Games: an analysis of usage of the Olympic Village ‘Polyclinic’ by competing athletes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235882045_The_London_2012_Summer_Olympic_Games_an_analysis_of_usage_of_the_Olympic_Village_’Polyclinic’_by_competing_athletes

2014: Healthcare Planning for the Olympics in London: A Qualitative Evaluation https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260950520_Healthcare_Planning_for_the_Olympics_in_London_A_Qualitative_Evaluation

Brisbane picked to host 2032 Olympics without a rival bid https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/brisbane-picked-host-2032-olympics-rival-bid-78963209