Endoscopy is often associated with cancer diagnosis, but other conditions are also diagnosed using various types of endoscopy – and many of these are being detected to an increasing extent. Gastroscopy, for example, is the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing coeliac disease, an increasingly common condition worldwide.

Coeliac disease is a condition whereby a person’s immune system reacts abnormally to gluten, a protein found in wheat and other grains, and causes damage to the small bowel. This in turn can lead to various gastrointestinal and malabsorptive symptoms. If the condition is not diagnosed or treated properly, this can lead to serious health consequences.

How common is coeliac disease?

It is estimated that coeliac disease affects on average around 1 in 70 Australians. However, most people with the condition do not have a medical diagnosis – as many as 80% of those living with coeliac are thought to remain undiagnosed.

Improvements in testing technology for coeliac disease over the last decade has revealed that coeliac disease is more widespread than previously thought. Originally considered to affect primarily white Caucasian populations, research has revealed that the condition is present globally and that the highest prevalence of coeliac disease anywhere in the world has in fact been found in northern Africa.

More people are also being diagnosed now compared with 10 years ago. A recent global study found new diagnosis of coeliac was up more than 7.5% each year, and found the pattern of increasing incidence over time was consistent across geography, sex and age, although the increase was slightly higher in women and children.

Although the increase in the number of people diagnosed in recent years can be partially attributed to improved awareness of the condition and greater access to testing, a true increase in the incidence of coeliac disease globally is widely acknowledged. This is contributing to an increasing burden on healthcare systems, including higher demand for endoscopy.

Diagnosis via gastroscopy

One reason only 20% of those with the condition are medically diagnosed is that up to 50% of patients with coeliac disease are thought to be asymptomatic. The condition is not routinely screened for; it is only picked up when symptoms are reported and investigated. And even then a diagnosis can take several years, as the symptoms are so diverse.

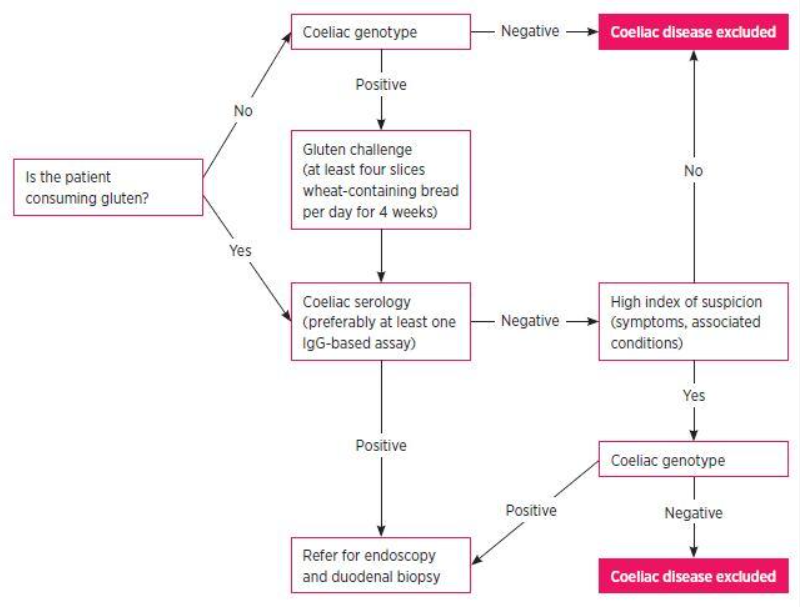

As many as 99% of patients who get the disease have a genetic predisposition, but approximately half of the Australian population carry the genes, so this is not a marker for coeliac disease on its own. Genotype testing can, however, be used to exclude coeliac disease when the diagnosis is in doubt.

The immune response to coeliac disease produces antibodies that can be measured. But although antibody testing has a high sensitivity and specificity, false negative and false positive tests occur in approximately 5% of tests. Therefore, the only way to obtain a definitive diagnosis requires gastroscopy and a duodenal biopsy, during which potential damage to the lining of the small bowel is investigated.

Figure – Diagnosis of coeliac disease

Source: Testing for coeliac disease

Historically, many patients with suspected coeliac disease were never referred or medically diagnosed but advised to instead adopt a gluten free diet to see if symptoms improved. Although this is still the case today, an increasing number of patients now move on to a definitive diagnosis via a gastroscopy.

Consequences of undiagnosed coeliac

The symptoms of the disease are mainly gastrointestinal, such as nausea, abdominal pain and mouth ulcers, but also include weight loss, fatigue, abnormal liver function tests and vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

The long term consequences of untreated coeliac disease include poor health generally, systemic inflammation, poor nutrition or malabsorption of nutrients, and it has been linked to early onset osteoporosis, infertility, miscarriage, depression and dental enamel defects. Timely diagnosis and a lifelong, strict gluten free diet can prevent or reverse many of the associated health conditions.

By removing the cause of the disease, the small bowel lining is allowed to heal and symptoms allowed to resolve, although a relapse will occur if gluten is reintroduced into the diet. However, commencing a strict life-long gluten-free diet without a definite diagnosis of coeliac disease could have consequences of its own, and since blood tests have a high false positive rate, a biopsy is increasingly recommended for all patients to confirm the diagnosis.

Other sources of endoscopy demand

Although gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is not generally a dangerous condition, its prevalence is increasing as the population is ageing and obesity levels are rising, and a gastroscopy may be performed to rule out a more serious condition.

Helicobacter (pylori), which can cause pain and stomach ulcers, and may increase the risk of getting stomach cancer, is also detected using a gastroscope. Although stomach cancer and oesophageal cancer are uncommon in the Australian population, people with symptoms may need a gastroscopy to rule them out.

In a similar way, changes caused by Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition where the lining of the lower part of the oesophagus changes, and signs of liver disease can be seen during a gastroscopy. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are some of the conditions that may be detected through a colonoscopy.

Early detection, prevention and treatment of bowel cancer is one of the main reasons that colonoscopies are performed. In Australia, bowel cancer is the most commonly diagnosed internal cancer.

Endoscopy demand is up

The number of endoscopies performed continues to increase year-on-year. Official data from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare shows that between 2016/17 and 2018/19, the number of endoscopy procedures increased by as much as 12%. But demand appears to be increasing even faster.

The impact of Covid-19 has been significant in some countries that faced long periods of cancellations. In Australia, which was less severely affected by the initial outbreak, screening colonoscopy was largely continued as part of the national bowel cancer screening programme. But even so, a substantial reduction in endoscopy activity did also occur here.

A new study has revealed that 66% fewer procedures were performed during Covid-19, with colonoscopy reduced to 46% of pre-Covid levels and gastroscopy to 25%.

Although cancer-related appointments have continued through the pandemic and many states have begun to catch up on the backlog, questions remain about the true impact on endoscopy services. The number of visits to primary care for gastrointestinal symptoms will need to be evaluated, but have fallen over the past year.

The added burden of more frequent referrals to gastroenterologists for coeliac disease and other less serious conditions, driven by improvements to blood tests, greater awareness and increasing screening of these conditions, means continuing to perform diagnostic endoscopic procedures above a minimum threshold may be critical to prevent a waiting lists escalating beyond acceptable levels in the near future.